Alongside this, developed countries have gone through a 'demographic transition', where population size is in some instances decreasing. In many ways, demographic change is explained closely in relation to development, non more so than in relation to 'overpopulation'.

Here's a quick overview of what we'll look at...

- The meaning of demographic change

- Some examples of demographic change

- A look at demographic change issues

- Causes of demographic change

- The impact of demographic change

Let's get started!

Demographic change: meaning

If demography is the study of human populations, then demographic change is about how human populations change over time. For example, we may look at differences in population size or population structure by sex ratios, age, ethnicity make-up, etc.

Demographic change is the study of how human populations change over time.

Population size is influenced by 4 factors:

- Birth rate (BR)

- Death rate (DR)

- Infant mortality rate (IMR)

- Life expectancy (LE)

On the other hand, population structure is affected by a myriad of factors. For example, it is affected by:

migration patterns

government policies

the changing status of children

a shift in cultural values (including the role of women in the workforce)

different levels of health education

access to contraception

Hopefully, you can start to see how demographic change relates to the development and what the causes and/or impacts might be. If not, keep reading below!

How does demographic change relate to development?

Demographic change is talked about most in relation to population growth. It is the discussions about the causes and consequences of population growth that relate to aspects of development.

Levels of female literacy are a social indicator of development. Levels of female literacy have been shown to directly affect the IMR and the BR, which in turn affects the degree of population growth in a country.

Fig. 1 - Levels of female literacy are a social indicator of development.

Developed MEDCs and developing LEDCs

Alongside this, the discussion can be split between understanding the significance, trends and causes of demographic change in (1) developed MEDCs and (2) developing LEDCs.

In today's developed countries, demographic change has largely followed a similar pattern. During industrialisation and urbanisation, developed countries went through a 'demographic transition' from high birth and death rates, with low life expectancy, to low birth and death rates, with high life expectancy.

In other words, MEDCs have gone from high population growth to extremely low levels and (in some instances), are now seeing population decline.

Examples of developed countries (MEDCs) that have followed this transition pattern include the UK, Italy, France, Spain, China, the US and Japan.

If you're studying geography, then you'll have heard this process referred to as the 'Demographic Transition Model'.

Demographic Transition Model

The Demographic Transition Model (DTM) consists of 5 stages. It describes the changes in birth and death rates as a country goes through the process of 'modernisation'.Based on historic data from developed countries, it highlights how both birth and death rates fall as a country becomes more developed. To see this in action, compare the 2 images below. The first shows the DTM and the second shows the demographic transition of England and Wales from 1771 (the start of the industrial revolution) to 2015.

Whilst this is important to be aware of, as sociologists studying global development, we are here to understand demographic change as an aspect of development, rather than deep-dive into demography.

In short, we want to know:

- the factors behind demographic changes, and

- the different sociological views around world population growth.

So let's get to the crux of it.

Causes of demographic change

There are many causes of demographic change. Let's first look at developed countries.

Causes of demographic change in developed countries

Demographic changes in developed countries include a variety of factors that lowered birth and death rates.

Changing status of children as a cause of demographic change

The status of children transitioned from being a financial asset to a financial burden. As child rights were established, child labour was banned and compulsory education became widespread. Consequently, families incurred costs from having children as they were no longer financial assets. This lowered the birth rate.

Reduced need for families to have several children as a cause of demographic change

Reduced infant mortality rates and the introduction of social welfare (e.g. the introduction of a pension) meant families became less financially dependent on children later on in life. Consequently, families had fewer children on average.

Improvements in public hygiene as a cause of demographic change

The introduction of well-managed sanitation facilities (such as proper sewage removal systems) reduced the death rates from avoidable infectious diseases such as cholera and typhoid.

Improvements in health education as a cause of demographic change

More people become aware of unhealthy practices that lead to illness and more people gained a greater understanding of and access to contraception. Improvements in health education are directly responsible for reducing both the birth and death rates.

Improvements in healthcare, medicines and medical advances as a cause of demographic change

These increase the ability to overcome any infectious disease or illness that may develop at any point in our life, ultimately increasing the average life expectancy by reducing the death rate.

The introduction of the smallpox vaccine has saved countless lives. From 1900 onwards, until its global eradication in 1977, smallpox was responsible for the deaths of millions of people.

Expanding the argument to developing countries

The argument, particularly from modernisation theorists, is that these factors and outcomes will also occur as LEDCs 'modernise'.

The sequence, particularly from modernisation theorists, is as follows:

- As a country goes through the process of 'modernisation', there are improvements in the economic and social aspects of development.

- These improving aspects of development in turn reduce the birth rate, reduce the death rate and increase the average life expectancy of its citizens.

- Population growth over time slows down.

The argument is that it is the conditions of development present within the country that impact demographic change and affect population growth.

Examples of these conditions of development include; levels of education, levels of poverty, housing conditions, types of work, etc.

The impact of demographic change

Most of today's current talk around demographic change is about the rapid population growth occurring in many developing countries. In many instances, this impact of demographic change has been referred to as 'overpopulation'.

Overpopulation is when there are too many people to maintain a good standard of living for everyone with the available resources present.

But why is this important, and how did the concern arise?

Well, Thomas Malthus (1798) argued that the world's population would grow quicker than the world's food supply, leading to a point of crisis. For Malthus, he saw it as necessary to reduce the high birth rates that would otherwise lead to famine, poverty and conflict.

It was only in 1960, when Ester Boserup argued that technological advances would outpace the increase in population size - ‘necessity being the mother of invention’ - that Malthus' claim was effectively challenged. She predicted that as humans approached the point of running out of food supplies, people would respond with technological advances which would increase food production.

Malthus' argument led to a division on how we should understand demographic change issues. Put simply, a division grew between those that see poverty and lack of development as a cause or a consequence of high population growth: a 'chicken-and-egg' argument.

Let's explore both sides...

Demographic change issues: sociological perspectives

There are several views on the causes and consequences of population growth. The two we shall focus on are:

These can be split into those that see population growth as either a cause or a consequence of poverty and a lack of development.

Population growth as the cause of poverty

Let's look at how population growth causes poverty.

The Neo-Malthusian viewpoint on population growth

As mentioned above, Malthus argued that the world's population would grow quicker than the world's food supply. For Malthus, he saw it as necessary to halt the high birth rates that would otherwise lead to famine, poverty and conflict.

Modern followers - Neo-Malthusians - similarly see high birth rates and 'overpopulation' as the cause of many of the development-related problems today. For Neo-Malthusians, overpopulation causes not just poverty but also rapid (uncontrolled) urbanisation, environmental damage and the depletion of resources.

Robert Kaplan (1994) expanded this. He argued that these factors ultimately destabilise a nation and lead to social unrest and civil wars - a process he called 'new barbarism'.

Modernisation theory on population growth

Agreeing with Neo-Malthusian beliefs, Modernisation theorists provided a set of practices by which to curb population growth. They argue that:

Solutions to overpopulation should focus on reducing birth rates. Specifically, by changing the values and practices within developing countries.

The main focus of governments and aid should be around:

Family planning - free contraception and free access to abortion

Financial incentives to reduce the family size (e.g. Singapore, China)

Population growth as the consequence of poverty

Let's look at how population growth is the consequence of poverty.

The anti-Malthusian view on population growth

The anti-Malthusian view is that famine within developing countries is due to MEDCs extracting their resources; in particular, the use of their land for 'cash crops' such as coffee and cocoa.

The argument states that if developing countries used their own land to feed themselves rather than being exploited and exported into the world's global economy, they would have the capacity to feed themselves.

Alongside this, David Adamson (1986) argues:

- That the unequal distribution of resources as outlined above is the major cause of poverty, famine and malnutrition.

- Having a high number of children is rational for many families in developing countries; children can generate extra income. With no pension or social welfare, children cover the costs of providing care for their elders in old age. High infant mortality rates mean having more children is seen as necessary to increase the chances of at least one surviving into adulthood.

Dependency theory on population growth

Dependency theorists (or Neo-Malthusians) also argue that the education of women is central to reducing birth rates. Educating women results in:

Increased awareness around health problems: awareness creates action, which reduces infant mortality

Increased women's autonomy over their own bodies and their own fertility

Easier access to (and improvement in understanding of) contraception

Consequently, aid should first and foremost be directed at tackling the causes of population growth, namely, poverty and high infant/child mortality rates. The way to achieve this is by providing better and more accessible healthcare services and improving educational outcomes for both sexes.

Demographic change example

From 1980 to 2015, China introduced the 'one-child policy'. It stopped an estimated 400 million children from being born!

China's one-child policy has undoubtedly achieved its aims of curbing population growth and in that time period, China has become a global superpower - its economy is now the second-largest in the world. But was it really a success?

Due to the one-child-per-family restrictions, several consequences have occurred...

- A preference for males over females has led to millions of more men than women in China and countless sex-based abortions (gendercide).

- The majority of families still rely on their children for financial support in later life; this is harder to do with increases in life expectancy. This has been referred to as the 4-2-1 model, where 1 child is now responsible for up to 6 elders in later life.

- Birth rates have continued to decline as working conditions and unaffordable childcare costs prevent many from raising children.

Fig. 2 - China has had a one-child policy as a result of demographic change.

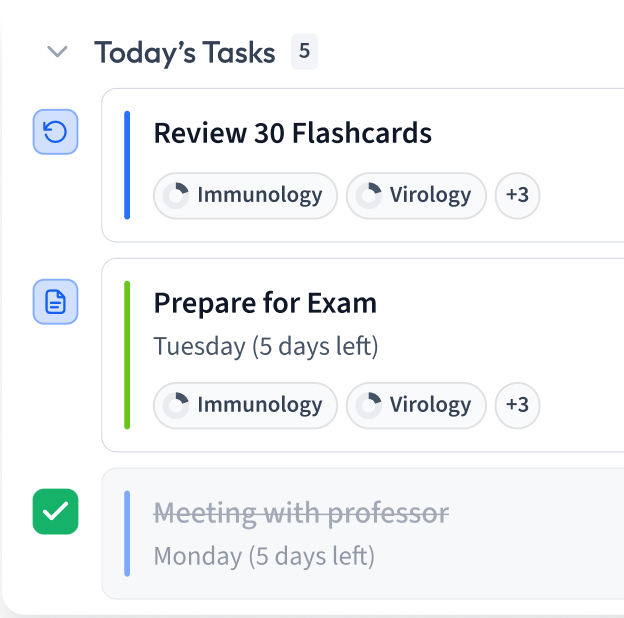

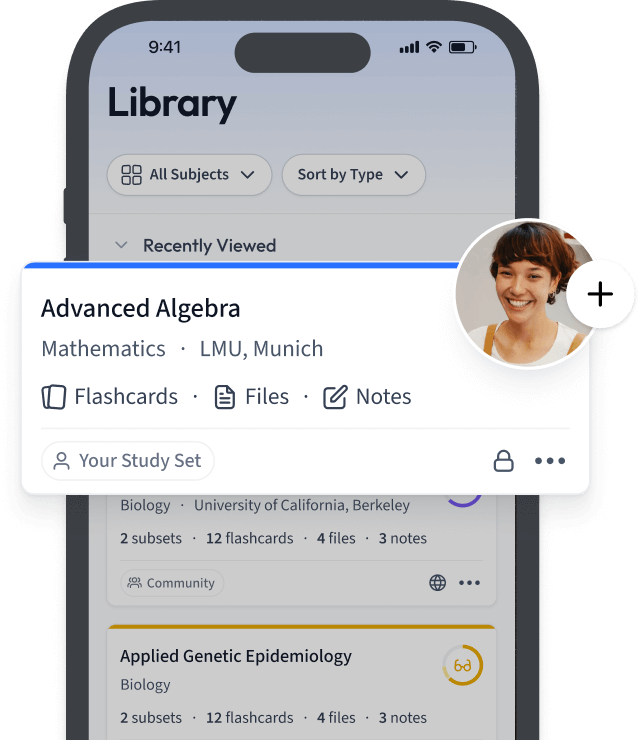

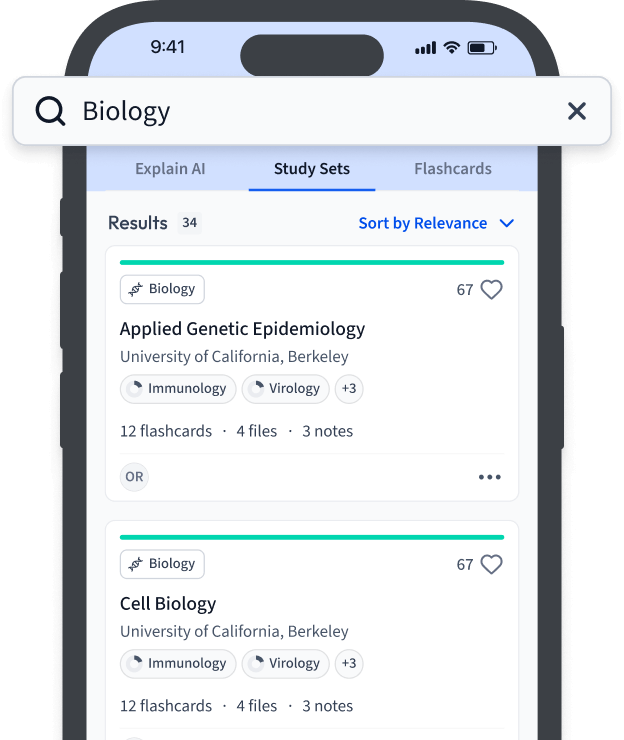

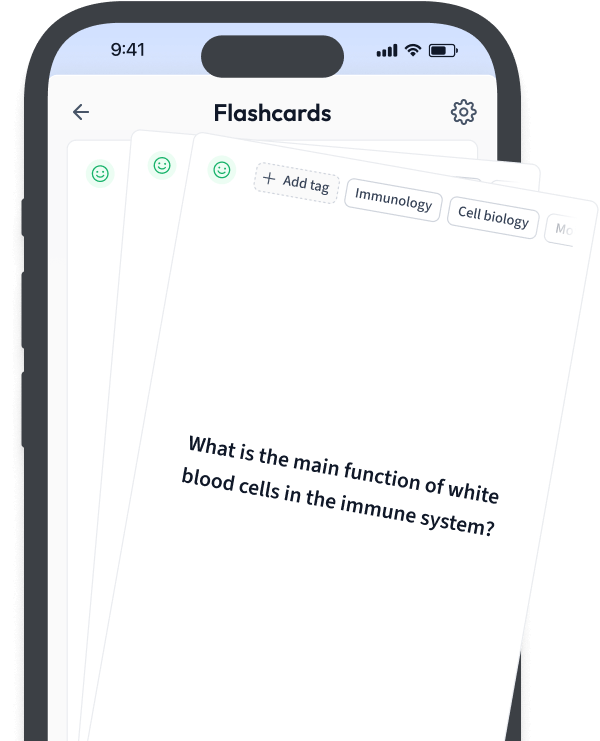

Access millions of flashcards designed to help you ace your studies

Sign up for free

Evaluation of the causes and impact of demographic change

In many ways, China's one-child policy highlights the limitations of modernisation theory and Neo-Malthusian arguments. Though it doesn't demonstrate whether high population growth is the cause or consequence of poverty, it highlights how a sole focus on cutting birth rates is misguided.

Underlying patriarchal views still present in Chinese society have led to mass female infanticide. A lack of social welfare has made it even more economically challenging to care for the elderly. The change in children from economic assets to an economic burden in many wealthy parts of China has meant the birth rate has stayed low, even after the policy was removed.

Counter to this, dependency theory and anti-Malthusian arguments highlight a more nuanced relationship between high population growth and global development. Further, the reasons provided, and the strategies suggested reflect more closely the demographic transition that occurred in many of the developed countries during the 18th to late 20th century.

Demographic Change - Key takeaways